Is There Such Thing As Unicellular Animal

| Unicellular organism | |

|---|---|

Valonia ventricosa, a species of alga with a diameter that ranges typically from 1 to 4 centimetres (0.4 to ane.vi in) is among the largest unicellular species |

A unicellular organism, too known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single jail cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms autumn into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and eukaryotic organisms. All prokaryotes are unicellular and are classified into bacteria and archaea. Many eukaryotes are multicellular, but some are unicellular such as protozoa, unicellular algae, and unicellular fungi. Unicellular organisms are thought to be the oldest form of life, with early on protocells possibly emerging 3.8–4.0 billion years ago.[one] [two]

Although some prokaryotes live in colonies, they are not specialised cells with differing functions. These organisms alive together, and each prison cell must bear out all life processes to survive. In contrast, even the simplest multicellular organisms take cells that depend on each other to survive.

Nigh multicellular organisms have a unicellular life-wheel phase. Gametes, for instance, are reproductive unicells for multicellular organisms.[iii] Additionally, multicellularity appears to have evolved independently many times in the history of life.

Some organisms are partially unicellular, like Dictyostelium discoideum. Additionally, unicellular organisms tin can be multinucleate, like Caulerpa, Plasmodium, and Myxogastria.

Evolutionary hypothesis [edit]

Primitive protocells were the precursors to today's unicellular organisms. Although the origin of life is largely even so a mystery, in the currently prevailing theory, known as the RNA world hypothesis, early RNA molecules would take been the footing for catalyzing organic chemical reactions and self-replication.[4]

Compartmentalization was necessary for chemic reactions to be more likely equally well as to differentiate reactions with the external environment. For example, an early on RNA replicator ribozyme may accept replicated other replicator ribozymes of different RNA sequences if not kept separate.[v] Such hypothetic cells with an RNA genome instead of the usual DNA genome are called 'ribocells' or 'ribocytes'.[four]

When amphiphiles like lipids are placed in water, the hydrophobic tails aggregate to form micelles and vesicles, with the hydrophilic ends facing outwards.[2] [five] Primitive cells likely used cocky-assembling fatty-acid vesicles to separate chemical reactions and the surroundings.[5] Because of their simplicity and power to self-assemble in water, it is likely that these simple membranes predated other forms of early biological molecules.[2]

Prokaryotes [edit]

Prokaryotes lack membrane-spring organelles, such equally mitochondria or a nucleus.[6] Instead, most prokaryotes have an irregular region that contains DNA, known every bit the nucleoid.[vii] Most prokaryotes take a single, circular chromosome, which is in dissimilarity to eukaryotes, which typically have linear chromosomes.[8] Nutritionally, prokaryotes take the ability to utilize a wide range of organic and inorganic textile for use in metabolism, including sulfur, cellulose, ammonia, or nitrite.[9] Prokaryotes are relatively ubiquitous in the environment and some (known as extremophiles) thrive in extreme environments.

Bacteria [edit]

Modern stromatolites in Shark Bay, Western Australia. It can take a century for a stromatolite to grow five cm.[10]

Bacteria are 1 of the world's oldest forms of life, and are found well-nigh everywhere in nature.[9] Many common bacteria have plasmids, which are short, circular, self-replicating DNA molecules that are split up from the bacterial chromosome.[11] Plasmids can carry genes responsible for novel abilities, of electric current disquisitional importance being antibiotic resistance.[12] Bacteria predominantly reproduce asexually through a process chosen binary fission. Nevertheless, about 80 different species can undergo a sexual process referred to as natural genetic transformation.[13] Transformation is a bacterial procedure for transferring DNA from one jail cell to some other, and is manifestly an adaptation for repairing Dna harm in the recipient cell.[14] In addition, plasmids can be exchanged through the employ of a pilus in a process known every bit conjugation.[12]

The photosynthetic blue-green alga are arguably the virtually successful bacteria, and changed the early on atmosphere of the world by oxygenating it.[15] Stromatolites, structures made up of layers of calcium carbonate and trapped sediment left over from cyanobacteria and associated community bacteria, left behind extensive fossil records.[15] [sixteen] The being of stromatolites gives an excellent tape as to the development of blue-green alga, which are represented across the Archaean (4 billion to 2.5 billion years agone), Proterozoic (two.v billion to 540 one thousand thousand years ago), and Phanerozoic (540 million years agone to present 24-hour interval) eons.[16] Much of the fossilized stromatolites of the world can be found in Western Commonwealth of australia.[16] There, some of the oldest stromatolites accept been found, some dating back to about 3,430 million years ago.[16]

Clonal aging occurs naturally in bacteria, and is apparently due to the accumulation of impairment that can happen even in the absence of external stressors.[17]

Archaea [edit]

A bottom-domicile community institute deep in the European Arctic.[18]

Hydrothermal vents release rut and hydrogen sulfide, allowing extremophiles to survive using chemolithotrophic growth.[nineteen] Archaea are by and large similar in advent to bacteria, hence their original classification as bacteria, only have significant molecular differences well-nigh notably in their membrane structure and ribosomal RNA.[xx] [21] Past sequencing the ribosomal RNA, it was found that the Archaea most likely split from leaner and were the precursors to modern eukaryotes, and are really more phylogenetically related to eukaryotes.[21] As their name suggests, Archaea comes from a Greek word archaios, significant original, ancient, or primitive.[22]

Some archaea inhabit the most biologically inhospitable environments on globe, and this is believed to in some means mimic the early, harsh weather that life was likely exposed to[ commendation needed ]. Examples of these Archaean extremophiles are as follows:

- Thermophiles, optimum growth temperature of 50 °C-110 °C, including the genera Pyrobaculum, Pyrodictium, Pyrococcus, Thermus aquaticus and Melanopyrus. [23]

- Psychrophiles, optimum growth temperature of less than 15 °C, including the genera Methanogenium and Halorubrum. [23]

- Alkaliphiles, optimum growth pH of greater than 8, including the genus Natronomonas.[23] [24]

- Acidophiles, optimum growth pH of less than 3, including the genera Sulfolobus and Picrophilus.[23] [25]

- Piezophiles, (besides known every bit barophiles), prefer loftier pressure level upward to 130 MPa, such as deep bounding main environments, including the genera Methanococcus and Pyrococcus.[23]

- Halophiles, grow optimally in high salt concentrations between 0.2 One thousand and 5.2 M NaCl, including the genera Haloarcula, Haloferax, Halococcus.[23] [26]

Methanogens are a significant subset of archaea and include many extremophiles, but are also ubiquitous in wetland environments equally well as the ruminant and hindgut of animals.[27] This process utilizes hydrogen to reduce carbon dioxide into methane, releasing free energy into the usable course of adenosine triphosphate.[27] They are the only known organisms capable of producing methane.[28] Under stressful ecology atmospheric condition that cause Dna damage, some species of archaea aggregate and transfer Dna betwixt cells.[29] The function of this transfer appears to be to supercede damaged DNA sequence information in the recipient cell by undamaged sequence information from the donor cell.[30]

Eukaryotes [edit]

Eukaryotic cells incorporate membrane spring organelles, such every bit mitochondria, a nucleus, and chloroplasts. Prokaryotic cells probably transitioned into eukaryotic cells betwixt 2.0 and 1.4 billion years ago.[31] This was an important footstep in evolution. In contrast to prokaryotes, eukaryotes reproduce past using mitosis and meiosis. Sexual activity appears to be a ubiquitous and ancient, and inherent aspect of eukaryotic life.[32] Meiosis, a truthful sexual process, allows for efficient recombinational repair of Dna damage [14] and a greater range of genetic diversity by combining the Dna of the parents followed by recombination.[31] Metabolic functions in eukaryotes are more specialized also by sectioning specific processes into organelles.[ citation needed ]

The endosymbiotic theory holds that mitochondria and chloroplasts take bacterial origins. Both organelles contain their own sets of DNA and accept bacteria-similar ribosomes. It is likely that modern mitochondria were in one case a species similar to Rickettsia, with the parasitic ability to enter a jail cell.[33] However, if the bacteria were capable of respiration, it would accept been beneficial for the larger cell to allow the parasite to alive in return for energy and detoxification of oxygen.[33] Chloroplasts probably became symbionts through a similar prepare of events, and are nearly likely descendants of cyanobacteria.[34] While not all eukaryotes accept mitochondria or chloroplasts, mitochondria are plant in most eukaryotes, and chloroplasts are found in all plants and algae. Photosynthesis and respiration are essentially the reverse of one another, and the advent of respiration coupled with photosynthesis enabled much greater admission to energy than fermentation lone.[ citation needed ]

Protozoa [edit]

Paramecium tetraurelia, a ciliate, with oral groove visible

Protozoa are largely defined by their method of locomotion, including flagella, cilia, and pseudopodia.[35] While there has been considerable debate on the nomenclature of protozoa caused past their sheer diversity, in i organization in that location are currently 7 phyla recognized under the kingdom Protozoa: Euglenozoa, Amoebozoa, Choanozoa sensu Condescending-Smith, Loukozoa, Percolozoa, Microsporidia and Sulcozoa.[36] [37] Protozoa, like plants and animals, can be considered heterotrophs or autotrophs.[33] Autotrophs like Euglena are capable of producing their energy using photosynthesis, while heterotrophic protozoa consume food by either funneling it through a mouth-like gullet or engulfing information technology with pseudopods, a form of phagocytosis.[33] While protozoa reproduce mainly asexually, some protozoa are capable of sexual reproduction.[33] Protozoa with sexual adequacy include the pathogenic species Plasmodium falciparum, Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma brucei, Giardia duodenalis and Leishmania species.[fourteen]

Ciliophora, or ciliates, are a group of protists that utilize cilia for locomotion. Examples include Paramecium, Stentors, and Vorticella.[38] Ciliates are widely arable in well-nigh all environments where water tin be found, and the cilia crush rhythmically in gild to propel the organism.[39] Many ciliates have trichocysts, which are spear-like organelles that tin exist discharged to catch prey, anchor themselves, or for defense.[40] [41] Ciliates are too capable of sexual reproduction, and apply 2 nuclei unique to ciliates: a macronucleus for normal metabolic control and a separate micronucleus that undergoes meiosis.[40] Examples of such ciliates are Paramecium and Tetrahymena that likely employ meiotic recombination for repairing Dna damage acquired under stressful conditions.[ citation needed ]

The Amebozoa apply pseudopodia and cytoplasmic flow to move in their surround. Entamoeba histolytica is the crusade of amebic dysentery.[42] Entamoeba histolytica appears to exist capable of meiosis.[43]

Unicellular algae [edit]

A scanning electron microscope paradigm of a diatom

Unicellular algae are plant-similar autotrophs and contain chlorophyll.[44] They include groups that have both multicellular and unicellular species:

- Euglenophyta, flagellated, mostly unicellular algae that occur often in fresh water.[44] In contrast to most other algae, they lack cell walls and can exist mixotrophic (both autotrophic and heterotrophic).[44] An instance is Euglena gracilis.

- Chlorophyta (green algae), mostly unicellular algae found in fresh water.[44] The chlorophyta are of particular importance considering they are believed to be about closely related to the evolution of country plants.[45]

- Diatoms, unicellular algae that have siliceous prison cell walls.[46] They are the virtually abundant class of algae in the ocean, although they can exist found in fresh water likewise.[46] They account for about 40% of the world's primary marine product, and produce about 25% of the earth's oxygen.[47] Diatoms are very diverse, and contain near 100,000 species.[47]

- Dinoflagellates, unicellular flagellated algae, with some that are armored with cellulose.[48] Dinoflagellates can exist mixotrophic, and are the algae responsible for scarlet tide.[45] Some dinoflagellates, like Pyrocystis fusiformis, are capable of bioluminescence.[49]

Unicellular fungi [edit]

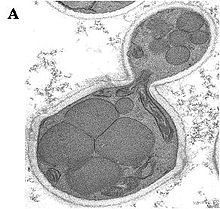

Unicellular fungi include the yeasts. Fungi are institute in about habitats, although most are plant on land.[l] Yeasts reproduce through mitosis, and many apply a process called budding, where well-nigh of the cytoplasm is held past the mother cell.[50] Saccharomyces cerevisiae ferments carbohydrates into carbon dioxide and alcohol, and is used in the making of beer and breadstuff.[51] S. cerevisiae is also an of import model organism, since it is a eukaryotic organism that's piece of cake to grow. It has been used to research cancer and neurodegenerative diseases as well as to understand the jail cell wheel.[52] [53] Furthermore, inquiry using S. cerevisiae has played a central office in understanding the mechanism of meiotic recombination and the adaptive part of meiosis. Candida spp. are responsible for candidiasis, causing infections of the mouth and/or throat (known as thrush) and vagina (ordinarily chosen yeast infection).[54]

Macroscopic unicellular organisms [edit]

Most unicellular organisms are of microscopic size and are thus classified as microorganisms. However, some unicellular protists and bacteria are macroscopic and visible to the naked eye.[55] Examples include:

- Brefeldia maxima, a slime mold, examples take been reported upwardly to a centimetre thick with a surface area of over a square metre and weighed up to around 20 kg[56]

- Xenophyophores, protozoans of the phylum Foraminifera, are the largest examples known, with Syringammina fragilissima achieving a diameter of up to 20 cm (7.9 in)[57]

- Nummulite, foraminiferans

- Valonia ventricosa, an alga of the form Chlorophyceae, tin reach a diameter of one to four cm (0.4 to 2 in)[58] [59]

- Acetabularia, algae

- Caulerpa, algae,[60] [ unreliable source? ] may grow to 3 metres long[61]

- Gromia sphaerica, amoeba, 5 to 38 mm (0.2 to one in)[61]

- Thiomargarita namibiensis is the largest bacterium, reaching a diameter of upward to 0.75 mm

- Epulopiscium fishelsoni, a bacterium

- Stentor, ciliates nicknamed trumpet animalcules

Come across also [edit]

- Abiogenesis

- Asexual reproduction

- Colonial organism

- Individuality in biology

- Largest organisms

- Modularity in biology

- Multicellular organism

- Sexual reproduction

- Superorganism

References [edit]

- ^ An Introduction to Cells, ThinkQuest, retrieved 2013-05-30

- ^ a b c Pohorille, Andrew; Deamer, David (2009-06-23). "Self-assembly and part of primitive cell membranes". Research in Microbiology. 160 (vii): 449–456. doi:ten.1016/j.resmic.2009.06.004. PMID 19580865.

- ^ Coates, Juliet C.; Umm-Due east-Aiman; Charrier, Bénédicte (2015-01-01). "Understanding "green" multicellularity: do seaweeds concur the key?". Frontiers in Plant Science. 5: 737. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00737. PMC4299406. PMID 25653653.

- ^ a b Lane N (2015). The Vital Question – Energy, Development, and the Origins of Circuitous Life . WW Norton. p. 77. ISBN978-0-393-08881-six.

- ^ a b c "Exploring Life'south Origins: Fatty Acids". exploringorigins.org . Retrieved 2015-10-28 .

- ^ "Prokaryotes". webprojects.oit.ncsu.edu . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ Kleckner, Nancy; Fisher, Jay M.; Stouf, Mathieu; White, Martin A.; Bates, David; Witz, Guillaume (2014-12-01). "The bacterial nucleoid: nature, dynamics and sister segregation". Current Opinion in Microbiology. Growth and development: eukaryotes/ prokaryotes. 22: 127–137. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.10.001. PMC4359759. PMID 25460806.

- ^ "Eukaryotic Chromosome Structure | Science Primer". scienceprimer.com . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b Smith, Dwight G (2015). Leaner . Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. ISBN978-1-58765-084-0.

- ^ "Nature Fact Sheets – Stromatolites of Shark Bay » Shark Bay". www.sharkbay.org.au . Retrieved 2015-xi-22 .

- ^ "Conjugation (prokaryotes)". www.nature.com . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b Cui, Yanhua; Hu, Tong; Qu, Xiaojun; Zhang, Lanwei; Ding, Zhongqing; Dong, Aijun (2015-06-10). "Plasmids from Food Lactic Acid Leaner: Diversity, Similarity, and New Developments". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 16 (6): 13172–13202. doi:10.3390/ijms160613172. PMC4490491. PMID 26068451.

- ^ Johnston C, Martin B, Fichant Chiliad, Polard P, Claverys JP (2014). "Bacterial transformation: distribution, shared mechanisms and divergent control". Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12 (three): 181–96. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3199. PMID 24509783. S2CID 23559881.

- ^ a b c Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol; Michod, Richard Due east. (Jan 2018). "Sexual practice in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 57: eight–25. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2017.ten.024. PMID 29111273.

- ^ a b "Fossil Tape of the Cyanobacteria". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b c d McNamara, Kenneth (2009-09-01). Stromatolites. Western Australian Museum. ISBN978-one-920843-88-five.

- ^ Łapińska, U; Glover, Thousand; Capilla-Lasheras, P; Young, AJ; Pagliara, South (2019). "Bacterial ageing in the absence of external stressors". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 374 (1786): 20180442. doi:10.1098/rstb.2018.0442. PMC6792439. PMID 31587633.

- ^ "NOAA Ocean Explorer: Arctic Exploration 2002: Groundwork". oceanexplorer.noaa.gov . Retrieved 2015-xi-22 .

- ^ Barton, Larry 50.; Fardeau, Marie-Laure; Fauque, Guy D. (2014-01-01). Hydrogen sulfide: a toxic gas produced by dissimilatory sulfate and sulfur reduction and consumed past microbial oxidation. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. pp. 237–277. doi:x.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_10. ISBN978-94-017-9268-iv. ISSN 1559-0836. PMID 25416397.

- ^ "Archaea". www.microbeworld.org . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b "Archaeal Ribosomes". www.els.net . Retrieved 2015-xi-22 .

- ^ "archaea | prokaryote". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b c d eastward f Gupta, G.N.; Srivastava, Due south.; Khare, South.K.; Prakash, 5. (2014). "Extremophiles: An Overview of Microorganism from Extreme Surroundings". International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology. vii (two): 371. doi:10.5958/2230-732X.2014.00258.7. Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ Falb, Michaela; Pfeiffer, Friedhelm; Palm, Peter; Rodewald, Karin; Hickmann, Volker; Tittor, Jörg; Oesterhelt, Dieter (2005-10-01). "Living with two extremes: Conclusions from the genome sequence of Natronomonas pharaonis". Genome Enquiry. fifteen (10): 1336–1343. doi:10.1101/gr.3952905. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC1240075. PMID 16169924.

- ^ "Acidophiles". www.els.net . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ ""Extremophiles: Archaea and Bacteria" : Map of Life". world wide web.mapoflife.org . Retrieved 2015-11-22 .

- ^ a b "Methanogens". world wide web.vet.ed.ac.great britain . Retrieved 2015-xi-22 .

- ^ Hook, Sarah E.; Wright, André-Denis M.; McBride, Brian W. (2010-01-01). "Methanogens: methyl hydride producers of the rumen and mitigation strategies". Archaea. 2010: 945785. doi:10.1155/2010/945785. ISSN 1472-3654. PMC3021854. PMID 21253540.

- ^ van Wolferen M, Wagner A, van der Does C, Albers SV (2016). "The archaeal Ced system imports DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (9): 2496–501. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.2496V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513740113. PMC4780597. PMID 26884154.

- ^ Witzany, Guenther, ed. (2017). Biocommunication of Archaea. doi:x.1007/978-3-319-65536-nine. ISBN978-3-319-65535-2. S2CID 26593032.

- ^ a b Yett, Jay R. (2015). Eukaryotes. Salem Printing Encyclopedia of Science.

- ^ Speijer, D.; Lukeš, J.; Eliáš, Thousand. (2015). "Sexual activity is a ubiquitous, ancient, and inherent attribute of eukaryotic life". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United states of americaA. 112 (29): 8827–34. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.8827S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501725112. PMC4517231. PMID 26195746.

- ^ a b c d due east "Origin of Mitochondria". Nature. Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ "Endosymbiosis and The Origin of Eukaryotes". users.rcn.com . Retrieved 2015-eleven-23 .

- ^ Klose, Robert T (2015). Protozoa. Salem Printing Encyclopedia of Science.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M. (2015-04-29). "A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms". PLOS ONE. x (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC4418965. PMID 25923521.

- ^ "Protozoa". www.microbeworld.org . Retrieved 2015-xi-23 .

- ^ "Ciliophora: ciliates, move with cilia". www.microscope-microscope.org . Retrieved 2015-eleven-23 .

- ^ "Introduction to the Ciliata". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu . Retrieved 2015-xi-23 .

- ^ a b "ciliate | protozoan". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ Sugibayashi, Rika; Harumoto, Terue (2000-12-29). "Defensive function of trichocysts in Paramecium tetraurelia against heterotrich ciliate Climacostomum virens". European Journal of Protistology. 36 (four): 415–422. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(00)80047-four.

- ^ "amoeba | protozoan club". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2015-eleven-23 .

- ^ Kelso AA, Say AF, Sharma D, Ledford LL, Turchick A, Saski CA, Rex AV, Attaway CC, Temesvari LA, Sehorn MG (2015). "Entamoeba histolytica Dmc1 Catalyzes Homologous Deoxyribonucleic acid Pairing and Strand Exchange That Is Stimulated by Calcium and Hop2-Mnd1". PLOS ONE. ten (nine): e0139399. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1039399K. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0139399. PMC4589404. PMID 26422142.

- ^ a b c d "algae Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com manufactures about algae". world wide web.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2015-xi-23 .

- ^ a b "Algae – Biology Encyclopedia – cells, plant, body, human, organisms, cycle, life, used, specific". www.biologyreference.com . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ a b "siliceous jail cell walls". www.mbari.org . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ a b "Diatoms are the nearly important group of photosynthetic eukaryotes – Site du Genoscope". www.genoscope.cns.fr . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ "Algae Classification: DINOPHYTA". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- ^ "BL Web: Growing dinoflagellates at habitation". biolum.eemb.ucsb.edu . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ a b "Microbiology Online | Microbiology Society | About Microbiology – Introducing microbes – Fungi". world wide web.microbiologyonline.org.great britain . Retrieved 2015-xi-23 .

- ^ Alba-Lois, Luisa; Segal-Kischinevzky, Claudia (2010). "Yeast Fermentation and the Making of Beer and Vino". Nature Didactics. 3 (9): 17. Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ "Saccharomyces cerevisiae – MicrobeWiki". MicrobeWiki . Retrieved 2015-eleven-23 .

- ^ "Using yeast in biology". www.yourgenome.org . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ "Candidiasis | Types of Diseases | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov . Retrieved 2015-11-23 .

- ^ Max Planck Society Research News Release Accessed 21 May 2009

- ^ Ing, Bruce (1999). The myxomycetes of Uk and Ireland : an identification handbook. Slough, England: Richmond Pub. Co. p. 4. ISBN0855462515.

- ^ Researchers Place Mysterious Life Forms in the Desert. Accessed 2011-x-24.

- ^ Bauer, Becky (Oct 2008). "Gazing Balls in the Sea". All at Sea. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ John Wesley Tunnell; Ernesto A. Chávez; Kim Withers (2007). Coral reefs of the southern Gulf of Mexico. Texas A&M University Press. p. 91. ISBN978-1-58544-617-nine.

- ^ "What is the Largest Biological Jail cell? (with pictures)". Wisegeek.com. 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-03-01 .

- ^ a b Anne Helmenstine (2018-11-29). "What Is the Largest Unicellular Organism?". sciencenotes.org. Retrieved 2020-01-07 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicellular_organism

Posted by: walkerbegaid.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is There Such Thing As Unicellular Animal"

Post a Comment